The European projects pooling data to defeat COVID-19

Futuris travels to Marseille and Cambridge to look at two European projects pooling and sharing data to help the scientific community beat COVID-19.

While one part of the scientific world is struggling to fight the SARS-Cov2 virus, institutes like the European Virus Archive in Marseille are making sure pathogens like it still exist.

Twelve years since its launch, the EVA has become one of the most important databases in the world. It holds more than 3000 products, including viruses, test substances and other types of material.

[contfnewc]

[contfnewc]

[contfnewc]

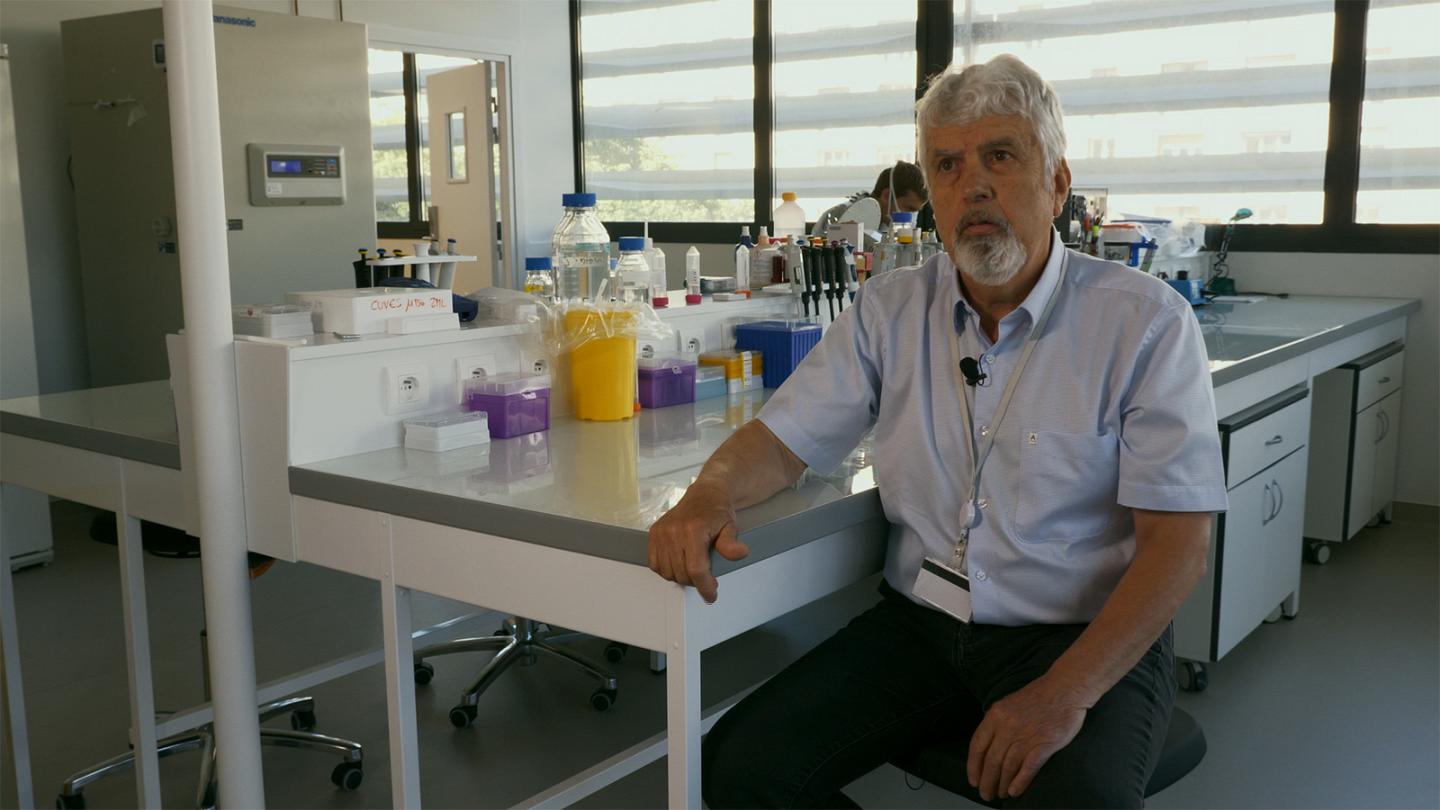

“This collection is a virtual collection. The idea was not to put all the viruses in the same place, like a Fort Knox of virology. The viruses remain in each laboratory,” says Jean Louis Romette, the EVA’s project coordinator.

This non-profit EU project makes it possible to rapidly supply scientists with the knowledge and material they need during a virus-related emergency.

“When the coronavirus appeared in China, our coronavirus researchers in the EVA organisation immediately saw that this virus was one of the SARS family, and they quickly developed a diagnostic system to detect the virus in patient samples,” Romette adds.

The Marseille-based Institute brings together nearly forty cutting-edge labs in human, animal and plant virological research. Its online catalog allows users to have access to genetic material and other various products. The coronavirus pandemic has led to a rise in online traffic: in just two months requests for diagnostic kits and viral strains have matched that which was received in the previous four years.

[contfnewc]

“When you have an emerging virus and there is very little data available about it, it’s very important to be able to compare it with other existing viruses, from the same family. So the bio-banks are useful in that sense, as they allow us to confront what is new with what already exists,” explains Christine Prat, EVA’s Market Strategy Developer.

The virological material is sent by research centres, laboratories, universities and specialised companies. Once it has arrived, it is tested, certified and filed in an online catalog, along with in-depth information thats key for the scientific community.

Bruno Coutard is responsible for collating what the EVA receives.

“We are increasing the amount of information through cell culture techniques. Using cell cultures, we are able to grow the virus, produce it and distinguish it. Distinguishing is what we call sequencing – to get the complete genome sequence of the virus. This enables us to associate this virus with a known virus species,” he says.

“During an epidemic you don’t have much time to work.”

Xavier Lamballerie, the Director of the EVA’s Emerging Virus Unit, says when an epidemic strikes it is important for scientists to be able to quickly rely on updated models and studies.

“During an epidemic you don’t have much time to work. Epidemics are usually short. If people work with different and poorly defined material, were never able to put all the studies together to compare them. The role of a reference collection like EVA is to provide very quickly, to as many partners as possible, the same products, very well identified, so that they can do research with them.”

The French institute has also been able to provide assistance to developing countries by sending reliable and simple to use testing kit.

“The EVA database allows us to prepare and react, to develop diagnostic tools, that are freeze-dried, so they are stable, at room temperature. They can be sent without being refrigerated. They are usable, extremely stable over time and laboratories can use them under conditions that are similar to those that are in the field,” says Virus Collection Supervisor, Remi Charrel.